What is the AI Act

The AI Act Regulation (EU) 2024/1689 laying down harmonised rules on artificial intelligence entered into force on August 1, 2024. In this context, the European Commission is promoting the “AI Pact”, seeking the GPAI and AI industry’s voluntary commitment and compliance to follow the AI Act and to start implementing its rules ahead of the legal deadline(s). EWC took part in the consultation of selecting topics in AI Pact seminars and made proposals for further activities and involce especially authors, artists and performers within the AI Pact exchanges.

On July 22, 2024, the European Commission published the draft AI Pact pledges pursuant to the EU Artificial Intelligence Act (the EU AI Act) and opened a consultation until 18 of August 2024 on the topics to be selected for further seminars related to the drafting of the AI Pact.

The EWC contributed within the consultation, quote:

From the perspective of one of the core groups negatively affected by GPAI and generative informatics, we, in representation of 50 organisations of writers and translators in the book sector, representing 220,000 individual authors of book works in 32 EU and non-Eu countries, kindly ask to acknowledge the following:

Currently, the aims of the AI pact are focused on the workflow and interests of AI developers, deployers, and providers, incl. on technical means. The implementation of the AI Act needs the holistic view on the full AI ecosystem:

(a) The sources of any so called „data“ – individuals, but in forefront writers, authors, artists and performers; (b) the collectors of copyright-protected works – corpora builders, sets-curators; and (c) the consumers and passive users of (G)AI products or AI-based decisions: the public.

In addition, it is necessary to develop a functioning technical system that makes both input and output traceable. It is also necessary to communicate to AI developers that machine-readable watermarking can be easily removed, and that GAI outputs require human-readable labelling. This is essential to enable fully informed decision-making and reception, as well as to avoid future (and occurring) remuneration fraud.

It is essential that the AI Pact helps to establish an end-to-end chain of responsibility and liability in which all parties involved are always informed and act in accordance with the law.

Finally, it is of great importance that AI developers realise that the design of the CDSM Directive Art 4 (as well as 3 and its implications of private partnerships between research institutions and commercial GPAI developers) is so controversial that a business model can by no means be built on the one-sided interpretation that Text and Data Mining is the same as GPAI and GenAI development, alone. Licensing and the respect for the decisions of all those who originate works are just as much a part of AI literacy as understanding of intellectual property law.

To the full EWC contribution: AI Pact EWC Contribution 240816

Banned applications

The new rules ban certain AI applications that threaten citizens’ rights, including biometric categorisation systems based on sensitive characteristics and untargeted scraping of facial images from the internet or CCTV footage to create facial recognition databases. Emotion recognition in the workplace and schools, social scoring, predictive policing (when it is based solely on profiling a person or assessing their characteristics), and AI that manipulates human behaviour or exploits people’s vulnerabilities will also be forbidden.

Law enforcement exemptions

The use of biometric identification systems (RBI) by law enforcement is prohibited in principle, except in exhaustively listed and narrowly defined situations. “Real-time” RBI can only be deployed if strict safeguards are met, e.g. its use is limited in time and geographic scope and subject to specific prior judicial or administrative authorisation. Such uses may include, for example, a targeted search of a missing person or preventing a terrorist attack. Using such systems post-facto (“post-remote RBI”) is considered a high-risk use case, requiring judicial authorisation being linked to a criminal offence.

Obligations for high-risk systems

Clear obligations are also foreseen for other high-risk AI systems (due to their significant potential harm to health, safety, fundamental rights, environment, democracy and the rule of law). Examples of high-risk AI uses include critical infrastructure, education and vocational training, employment, essential private and public services (e.g. healthcare, banking), certain systems in law enforcement, migration and border management, justice and democratic processes (e.g. influencing elections). Such systems must assess and reduce risks, maintain use logs, be transparent and accurate, and ensure human oversight. Citizens will have a right to submit complaints about AI systems and receive explanations about decisions based on high-risk AI systems that affect their rights.

Transparency requirements

General-purpose AI (GPAI) systems, and the GPAI models they are based on, must meet certain transparency requirements, including compliance with EU copyright law and publishing detailed summaries of the content used for training. The more powerful GPAI models that could pose systemic risks will face additional requirements, including performing model evaluations, assessing and mitigating systemic risks, and reporting on incidents.

Additionally, artificial or manipulated images, audio or video content (“deepfakes”) need to be clearly labelled as such.

Measures to support innovation and SMEs

Regulatory sandboxes and real-world testing will have to be established at the national level, and made accessible to SMEs and start-ups, to develop and train innovative AI before its placement on the market.

The EU Artificial Intelligence Act

The European Union’s new AI law came into force on August 1. Crucially, it sets requirements for different AI systems based on the level of risk they pose. The more risk an AI system poses for health, safety or human rights of people, the stronger requirements it has to meet.

The act contains a list of prohibited high-risk systems. This list includes AI systems that use subliminal techniques to manipulate individual decisions. It also includes unrestricted and real-life facial recognition systems used by by law enforcement authorities, similar to those currently used in China.

Other AI systems, such as those used by government authorities or in education and healthcare, are also considered high risk. Although these aren’t prohibited, they must comply with many requirements.

For example, these systems must have their own risk management plan, be trained on quality data, meet accuracy, robustness and cybersecurity requirements and ensure a certain level of human oversight.

Lower risk AI systems, such as various chatbots, need to comply with only certain transparency requirements. For example, individuals must be told they are interacting with an AI bot and not an actual person. AI-generated images and text also need to contain an explanation they are generated by AI, and not by a human.

Designated EU and national authorities will monitor whether AI systems used in the EU market comply with these requirements and will issue fines for non-compliance.

What is the timeline of obligations of AI Act?

In this episode of our new series on the AI Act, Rosemarie Blake and Ciara Anderson, Senior Associates in our Technology and Innovations Group, discuss the timeline for application of obligations and the different participants along the AI value chain.

]

]

Other countries are following suit

The EU is not alone in taking action to tame the AI revolution.Earlier this year the Council of Europe, an international human rights organisation with 46 member states, adopted the first international treaty requiring AI to respect human rights, democracy and the rule of law.

- Canada is also discussing the AI and Data Bill. Like the EU laws, this will set rules to various AI systems, depending on their risks.

- Instead of a single law, the US government recently proposed a number of different laws addressing different AI systems in various sectors.

- Australia can learn – and lead. In Australia, people are deeply concerned about AI, and steps are being taken to put necessary guardrails on the new technology.Last year, the federal government ran a public consultation on safe and responsible AI in Australia. It then established an AI expert group which is currently working on the first proposed legislation on AI.The government also plans to reform laws to address AI challenges in healthcare, consumer protection and creative industries.The risk-based approach to AI regulation, used by the EU and other countries, is a good start when thinking about how to regulate diverse AI technologies.

The European AI Office

Description from https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/ai-office

“At an institutional level, the AI Office works closely with the European Artificial Intelligence Board formed by Member State representatives and the European Centre for Algorithmic Transparency (ECAT) of the Commission.

The Scientific Panel of independent experts ensures a strong link with the scientific community. Further technical expertise is gathered in an Advisory Forum, representing a balanced selection of stakeholders, including industry, startups and SMEs, academia, think tanks and civil society. The AI Office may also partner up with individual experts and organisations. It will also create fora for cooperation of providers of AI models and systems, including general-purpose AI, and similarly for the open-source community, to share best practices and contribute to the development of codes of conduct and codes of practice.

The AI Office also oversees the AI Pact, which allows businesses to engage with the Commission and other stakeholders such as sharing best practices and joining activities. This engagement has started before the AI Act entered into force and will allow businesses to plan ahead and prepare for the full implementation of the AI Act. All this will be part of the European AI Alliance, a Commission initiative, to establish an open policy dialogue on AI.

Further initiatives to foster trustworthy AI development and uptake within the EU are mapped on the Coordinated Plan on AI.”

]

]

Around the world, governments are grappling with how best to manage the increasingly unruly beast that is artificial intelligence (AI).

This fast-growing technology promises to boost national economies and make completing menial tasks easier. But it also poses serious risks, such as AI-enabled crime and fraud, increased spread of misinformation and disinformation, increased public surveillance and further discrimination of already disadvantaged groups.

Recent AI Regulatory Developments in APAC

-

India was expected to include AI regulation as part of its proposed Digital India Act, although a draft of this proposed legislation is yet to be released. However, it was reported that a new AI advisory group has been formed, which will be tasked with (1) developing a framework to promote innovation in AI (including through India-specific guidelines promoting the development of trustworthy, fair, and inclusive AI) and (2) minimizing the misuse of AI. In March 2024, the government also released an Advisory on Due Diligence by Intermediaries/Platforms, which advises platforms and intermediaries to ensure that unlawful content is not hosted or published through the use of AI software or algorithms and requires platform providers to identify content that is AI-generated and explicitly inform users about the fallibility of such outputs.

-

Indonesia’s Deputy Minister of Communications and Informatics announced in March 2024 that preparations were underway for AI regulations that are targeted for implementation by the end of 2024. A focus of the regulations is expected to be on sanctions for misuse of AI technology, including those involving breaches of existing laws relating to personal data protection, copyright infringement, and electronic information.

-

Japan is in the preliminary stages of preparing its AI law, known as the Basic Law for the Promotion of Responsible AI. The government aims to finalize and propose the bill by the end of 2024. The bill looks likely to target only so‐called “specific AI foundational models” with significant social impact, and it touches on aspects such as accuracy and reliability (e.g., via safety verification and testing), cybersecurity of AI models and systems, and disclosure to users of AI capabilities and limitations. The framework also proposes collaboration with the private sector in implementing specific standards for these measures.

-

Malaysia is developing an AI code of ethics for users, policymakers, and developers of AI-based technology. The code outlines seven principles of responsible AI, which primarily focus on transparency in AI algorithms, preventing bias and discrimination by inclusion of diverse data sets during training, and evaluation of automated decisions to identify and correct harmful outcomes. There are presently no indications that the government is contemplating the implementation of AI-specific laws.

-

Singapore has similarly not announced plans to develop AI-specific laws. However, the government introduced the Model AI Governance Framework for Generative AI in May 2024, which sets out best practice principles on how businesses across the AI supply chain can responsibly develop, deploy, and use AI technology. Relatedly, the government-backed AI Verify Foundation has released AI Verify, a testing toolkit that developers and owners can use to assess and benchmark their AI system against internationally recognized AI governance principles. The government also recently revealed plans to introduce safety guidelines for generative AI model developers and app deployers, which are aimed at promoting end users’ rights through encouraging transparency in relation to how AI applications work (including what data is used, the results of testing, and any limitations of the AI model) and outline safety and trustworthiness attributes that should be tested prior to deployment.

-

South Korea’s AI law, the Act on Promotion of the AI Industry and Framework for Establishing Trustworthy AI, has passed the final stage of voting and is now under review by the National Assembly. Following an “allow first, regulate later” principle, it aims to promote the growth of the domestic AI industry but nevertheless imposes stringent notification requirements for certain “high risk AI” (those that have a significant impact on public health and fundamental rights).

-

Taiwan has published a draft AI law entitled the Basic Law on Artificial Intelligence. The draft bill is open for public consultation until September 13, 2024. It outlines a series of principles for research into development and application of AI and proposes certain mandatory standards aimed at protecting user privacy and security, such as specific AI security standards, disclosure requirements, and accountability frameworks.

-

Thailand has been developing draft AI legislation, notably the Draft Act on Promotion and Support for Artificial Intelligence (which creates an AI regulatory sandbox) and the Draft Royal Decree on Business Operations That Use Artificial Intelligence Systems (which outlines a risk-based approach to AI regulation by setting out differentiated obligations and penalties for categories of AI used by businesses). Like the approach taken in the EU AI Act, the Draft Royal Decree groups AI systems into three categories: unacceptable risk, high risk, and limited risk. The progress of both pieces of legislation is unclear, however, with no major developments reported in 2024.

-

Vietnam’s draft AI law, the Digital Technology Industry Law, is under public consultation until September 2, 2024. The draft sets out policies aimed at advancing the country’s digital technology industry, including government financial support for companies participating in or organizing programs aimed at improving their research and development capacity, as well as a regulatory sandbox framework. It also outlines prohibited AI practices, including the use of AI to classify individuals based on biometric data or social behavior. If enacted, it will apply to businesses operating in the digital technology industry (which includes information technology, AI systems, and big data companies).

AI is a double edged sword

AI is already widespread in human society. It is the basis of the algorithms that recommend music, films and television shows on applications such as Spotify or Netflix. It is in cameras that identify people in airports and shopping malls. And it is increasingly used in hiring, education and healthcare services.

But AI is also being used for more troubling purposes. It can create deepfake images and videos, facilitate online scams, fuel massive surveillance and violate our privacy and human rights.

For example, in November 2021 the Australian Information and Privacy Commissioner, Angelene Falk, ruled a facial recognition tool, Clearview AI, breached privacy laws by scraping peoples photographs from social media sites for training purposes. However, a Crikey investigation earlier this year found the company is still collecting photos of Australians for its AI database.

Cases such as this underscore the urgent need for better regulation of AI technologies. Indeed, AI developers have even called for laws to help manage AI risks.

Navigating the European Union Artificial Intelligence Act for Healthcare

]

]

The European Union (EU) has taken a critical step towards regulating artificial intelligence (AI) with the adoption of the AI Act by its 27 member states on March 13, 20241. First proposed in April 2021 by the European Commission2, the AI Act emerged from the growing recognition of AI’s transformative potential and the need to address associated risks and ethical concerns, building on previous EU initiatives, including the 2018 Coordinated Plan on AI3 and the 2020 White Paper on AI4. The Council issued its position in December 20225, followed by the European Parliament’s adoption of its negotiating position in June 20236. After revising the draft, the final negotiations between the Commission and Council resulted in a provisional agreement in December 2023, which was endorsed by Member States in February 20241.

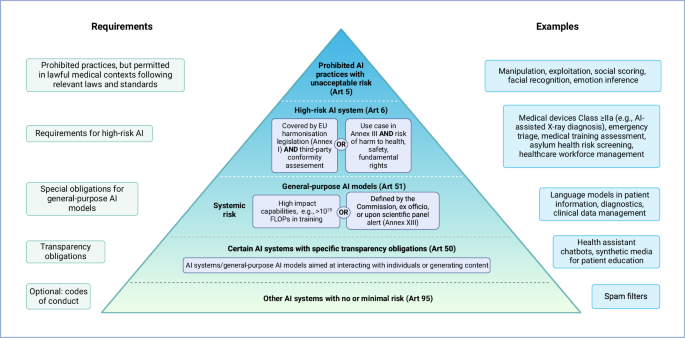

As the world’s first comprehensive legal framework specifically on AI, the AI Act aims to promote human-centred and trustworthy AI while protecting the health, safety, and fundamental rights of individuals from the potentially harmful effects of AI-enabled systems (Article (Art) 1 (1)). The Act sets out harmonised rules for the placing on the market, putting into service and use of AI systems and has become binding law in all EU Member States 20 days after its publication in the Official Journal of the EU (published on July 12th 2024), irrespective of existing national laws and guidelines on AI (Art 1 (2a), Art 113). Most parts of the regulation will take effect within 24 months, with prohibitions, i.e., bans on AI applications deemed to pose an unacceptable risk, taking effect already within 6 months (Art 113 (a–c)).

In its current form, the AI Act has a far-reaching scope, not only in the internal market but also extraterritorially, as it applies to all providers of AI systems in the EU market, regardless of where they are established or located (Art 2 (1a); see definitions of provider, deployer, and AI system in Table 1). In addition, the AI Act applies to providers and deployers of AI systems in third countries if the generated output is used in the Union (Art 2 (1c)). However, ‘output’ is not defined in the AI Act, and examples are vague, such as “[…] predictions, content, recommendations, or decisions that can influence physical or virtual environments […]” (Art 3 (1)). This suggests that any AI product could be subject to the AI Act if its output can be received in the Union, regardless of the provider’s or deployer’s intention or location. Finally, the AI Act also applies to “[…] deployers of AI systems that have their place of establishment or are located within the Union […]” (Art 2 (1b)). Therefore, deployers of AI systems within the EU, even if their models are not intended for the EU market, must comply with the AI Act regulations.

Table 1 Definitions of AI system, provider, deployer, and GPAI model and system in the EU AI Act Full size table

For the healthcare domain, the AI Act is particularly important, as other existing harmonisation legislation, such as the Medical Device Regulation (MDR; regulates products with an intended medical purpose on the EU market, classifying them from low-risk Class I (e.g., bandages) to high-risk Class III (e.g., implantable pacemaker)) or the In Vitro Diagnostic Medical Device Regulation (IVDR; regulates in vitro diagnostic devices with an intended medical purpose on the EU market, categorising them from Class A (low-risk, e.g., laboratory instruments) to Class D (high risk, e.g., products for detecting highly contagious pathogens such as Ebola)), do not explicitly cover medical AI applications. In addition, not all AI applications that can be adopted in the healthcare sector necessarily fall within the scope of the MDR or IVDR, e.g., general-purpose large language models (LLM) such as ChatGPT2,3.

Given the far-reaching impact of this regulation on the market, all stakeholders in the medical AI sector, including developers, providers, patients, and practitioners, can benefit from understanding its complex definitions, obligations, and requirements. Understanding the framework will help to clarify which models are covered by this regulation and the obligations that must be followed, ensuring that AI is implemented safely and responsibly, preventing potential harm, and ultimately driving innovation in medical AI. In this commentary, we navigate the most important aspects of the AI Act with a view to the healthcare sector and provide easy-to-follow references to the relevant chapters.

Get the latest KPMG thought leadership directly to your individual personalized dashboard

]

]

回到上一頁